The signadori exert themselves against Envy and the Eye by evoking the mystic forces of Christianity.Their intervention,

though differing in detail from one person and one locality to another, conforms to an esta-blished rite practised all over

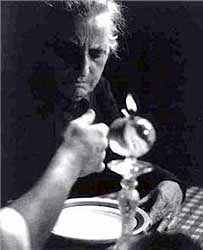

the island. The signadore, who is likely to be a woman, pours cold water into a white soup plate and makes the sign of

the cross above it three times with her right hand. She then lets fall into the water, again making the sign of the cross,

three drops of hot olive oil from the little finger of her left hand. The oil was traditionally taken from the glass or

metal lamp that stood on the mantlepiece; today it is scooped from any receptacle of heated oil.

, the particular signing that consists of

pointing to the four extremities of the holy cross.

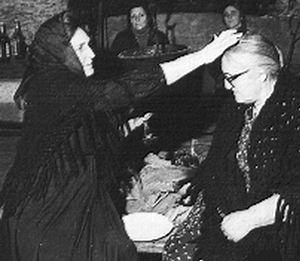

The plate containing the water and oil is sometimes held over the patient's head, sometimes laid on top of a lock of his

hair on a table, or placed on a table where he clasps it between his hands. The rite is performed in a ceremonial silence

during which the signadora, her eyes half-closed, seems to be entering a state of trance. In fact she is inaudibly reciting

one of her appropriate prayers. This must be learnt at or near midnight on

, that sacred night when God comes to visit men and evil influences are inoperative. They may also, Dorothy Carrington has

heard, be transmitted on the

Taught by grandparents to grandchildren, they are thought to be inspired by the spirits of ancestors. If

divulged by the signadori they lose their power.

The pattern made by the oil in the water reveals the patient's condition, his physical and mental health and whether or not

he is suffering from the Eye. The Eye is shown when the oil disperses in little blobs and refuses to coalesce in spite of

the prodding of the signadora's finger. If it is the consequence of an

the oil flows all over the plate.

The rite sometimes operates in such a way as to transfer the illness from patient to healer. The signadora is suddenly

stricken with headache, nausea, tears: she is infected by the Eye until it is captured in the oil and water and expelled

after she has broken the pattern with her finger and thrown the contents of the plate out of doors, or into the heart./

Women are numerous among the signadori. This must surely be attributed to the same

factors that have drawn women to mazzerisme: being a signadora

or a mazzera has offered them escape from the restricted, subordinate role allotted to them

by society. An example, in the words of Georges Ravis-Giordani( ethnologist): "They were expected to carry stones and mortar

to a site where a house was being built, so that the men had only to arrange the materials brought to them".It gave them as

well an opportunity to exercise innate psychic gifts.

According to Roccu Multedo the postulant must be a practising Catholic, the mother of a family and over forty. The great

majority of feminine signadori are indeed middle-aged or elderly, as though they had

adopted their profession after their children had grown up and left home.

The gift to dispel the Eye, like the proclivity to suffer from it, is said to run in certain families, the members of

which affect each other by daily contact, by contagion, as also happens among the mazzeri.

|

The signadori, devout Catholics, were not prosecuted by the Inquisition that operated

in Corsica between the mid-sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries, even though it had no hesitation in condemning women

for trying to heal. They survived and continued to perform their mission; perhaps precisely because, like the

mazzeri, they were too well respected to be denounced.

Signadori are not fortune-tellers. They can read thoughts and see into the present, but

only a very few of the most gifted can see the future, and then only the general drift of the patient's life, without

circumstantial detail.

Corsicans other than signadori tend to see only death in the future, albeit without

seeking that knowledge.

A cultured town-dwelling friend of Dorothy Carrington detected in an egg-shell the outline of a crucifix of a funeral

wreath; news of the death of a relative came the next day. Many people claim that the future can be seen in the shell

of an egg laid on the day of the Ascension, which is supposed to keep fresh for a year and to possess a protective magic

against illness and accident. Magic is likewise attributed to a certain herb - Sedum stellatum L. - which must be picked

on that morning before dawn and nailed to an inner wall of the house, where it will remain forty days in flower. It is

often seen in shepherds' cabins.

The shepherds are the people in Corsica most given to predicting the future, and who deliberately practise this art.

The occult faculties of the Corsicans, paradoxically, tend to wipe out their awareness of the future; what will happen

has for them already occurred./

The signadori do much to appease conflicts on the island, unobtrusively, using their own chosen methods. They take

no part in local quarrels, even when they well know what is going on in their communities. Their action is not

directed against individuals, but against the Eye, the Envy that is working throught them. Their aim is to restore

a harmony, psychic or physical, broken by the forces of destruction, by invoking those of Christianity.

Their prayers appeal to the great figures of the Christian

religion: "Le père Sauveur", God the Father; "Le Saint

Sauveur", Jesus Christ; John the Baptist; the Virgin Mary ( see also article about The Cult of the

Virgin Mary); Saint Joseph and Saint Anne. The meaning of their prayers is often evasive. A prayer to stanch blood is cast in sequence of declarations which pay tribute to the Virgin Mary and to the magical

quality of the number three: |

Madre Maria per mare venia

Tre lancia d'oro in manu tenia

Una lanciaia, l'altra feria

è l'altra u sangue stancia facia |

Mother Mary came by sea

She held three lances in her hand

One cut, the other wounded

And the other stopped the flow of blood |

Rather than prayers, the words recited by the signadori should be

termed incantations, as is indicated by a Corsican expression describing their rite,

incantesimo, while the signadori may be called "incantatora".

It cannot really be said that the incantations form a body of oral literature comparable to that of the voceri *) and

lamenti *), for they lack literary quality.

Roccu Multedo has found incantations in Italy. Incantations are used as well in the Scottish Highlands both in their lack

of adornment and their form. So the Holy Trinity is pitted against the Evil Eye.

If the incantations of the signadori seem, as

a whole, to emanate from medieval Christianity, it is hardly possible to determine their date.

The slow, painful penetration of Christianity was later threatened by Vandal and Saracen invasions, which must have

left deep scars on the Corsican psyche. The urgency and violence of the signadori's incantations

might suggest that they derive from such heroic times.

It was the Franciscans, seeking to mitigate the harshness of island life, who propagated the cult of the Virgin Mary, so

often appealed to by the signadori.

It would be imprudent to assume a Christian origin for the practices

of the signadori. The Evil Eye is much older than

Christianity. Their rites and prayers may well mask others, invoking forgotten pagan nature-spirits or divinities.

The signadori may have been active for as long a time as the mazzeri before they

Christianized their rites. The technique of divination with oil and water, widespread in the Mediterranean, is supposed

to date from the Chaldeans (7th-6th c. B.C.). It may not, however, have been originally used by

the signadori. One may bear in mind that the olive tree was introduced to

Corsica by the Greeks of antiquity. signadori of an earlier period may have employed

other substances.

Today, some throw into the water grains of wheat, or scraps of heather, or salt, reputedly magical, or melted wax or

lead. Berries of the lentisk, common in the Corsican maquis, can be crushed to produce oil, the so-called "oil of the poor".

Certain signadori can operate " a secca": "dry", by making the sign of the

cross on the patient's forehead, or in the air, standing in front of him so as to indicate his entire physical

configuration.

Observers of the Corsican scene regard the signadori as antithetical to

the mazzeri. The mazzeri bring death, the signadori

health; the mazzeri act surreptitiously, by night, in the maquis,

the signadori openly, by day, in their homes. One can add that whereas the

mazzeri act in a state of a dream, and under compulsion,

the signadori act deliberately, of their own free will.

However there is overlapping of roles. Dorothy Carrington heard of a woman of the southern Sartenais who some

twenty years ago practised as a mazzera by night and as a

signadora by day, to rid herself, she admitted, of a sense of guilt. Guilt such

as not infrequently torments the mazzeri, as has been told.

Mazzeri and signadori, it seems, once collaborated as weather-controllers. The

technique of the

signadori in this matter is perpetuated by the

shepherds-practitioners of the Niolu. The incantations she presents are not, strangely enough, designed to bring rain, but

to avert it, rain storms being more dreaded in that mountain area than drought.

Their main occupation is naturally the welfare of their livestock.

At the moment of the blessing of the flocks, water is sprinkled over the animals.But then the water is not

regarded as the abode of evil spirits, because it has been blessed, so that it has a holy virtue akin to that

of baptism.

Animals gone astray can be traced and recuperated by the appropriate formula, just as Saint Anthony is appealed

to all over Corsica for finding lost objects, with or without the aid of the signadori.

Cures can be evoked for the bites of poisonous insects: scorpions, and the zinefra, a venomous spider. Sunstroke,

a prevalent mountain malady, conjunctivitis and bronchitis are all subject to the treatment of

the signadori. In fact the Corsicans have inherited an arsenal of magical cures,

designed to combat every ill that can befall them, natural or supernatural. But for

the signadori all are supernatural, and therefore vulnerable to their rites and spells.

Only one misfortune is not susceptible to magic: against death there is no appeal.

*) voceri: songs in honour of the deceased

*) lamenti: laments for an unhappy situation, misfortune

Yvonne Peters

2004

Postscript:

There is so much more to know about these subjects, such as interesting stories told by mazzeri,

finzioni, signadori, and Corsicans who met them, and comparisons with other cultures.

If you are really interested, you shouldn't deprive yourself of the chance to read Dorothy Carrington's fascinating

book to know more about the magico-religious aspects of Corsican culture!

Legends & studies by Dorothy Carrington

Various aspects of the mazzeri's activities are enigmatic, obscure, belonging, as they do, to the world of dream.

Various aspects of the mazzeri's activities are enigmatic, obscure, belonging, as they do, to the world of dream. Belief in the Evil Eye is worldwide; the Corsican signadori have

parallels the world over.

Belief in the Evil Eye is worldwide; the Corsican signadori have

parallels the world over.

Mazzeri and signadori, it seems, once collaborated as weather-controllers. The

technique of the signadori in this matter is perpetuated by the

shepherds-practitioners of the Niolu. The incantations she presents are not, strangely enough, designed to bring rain, but

to avert it, rain storms being more dreaded in that mountain area than drought.

Mazzeri and signadori, it seems, once collaborated as weather-controllers. The

technique of the signadori in this matter is perpetuated by the

shepherds-practitioners of the Niolu. The incantations she presents are not, strangely enough, designed to bring rain, but

to avert it, rain storms being more dreaded in that mountain area than drought.